Long White Gypsy uses affiliate links and is a member of the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. If you make a purchase using one of these links, I may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. See my Privacy Policy for more information.

There’s nothing easy about starting a 3,000 km hike. Standing at Cape Reinga, looking out over the vast expanse of the Pacific, I wasn’t entirely convinced I could do it. Over the next four days, I would cross the first 100 kilometers of Te Araroa—through endless beaches, scorching dunes, and moments of real doubt. What I didn’t expect was how much each step, however painful, would push me deeper into this journey—both across the land and within myself.

Section Summary

Day 1: Cape Rēinga to Twilight Beach – 12.2km / 7.6mi – 4 hours

Day 2: Twilight Beach to Maunganui Bluff – 27.9km / 17.3mi

Day 3: Maunganui Bluff to Utea Park – 29.3km / 18.2mi

Day 4: Utea Park to Ahipara – 32.9km / 20.4mi

Dates: 4 Nov to 7 Nov 2019

Days: 4 total / 4 walking

Distance Covered: 102.3km / 63.6mi

Average Distance/Day: 25.6km / 15.9mi

TA Kilometres: 0km to 102.3km

Day 1: Cape Rēinga to Twilight Beach Campsite

Chapter 1: The First Step

The sun rises on 4 November 2019, but the nerves haven’t left me.

I sit with the other hikers at Utea Park, trying to hide the fear that grips me. It’s not working. After a last shower and packing up my spare food to leave with Pauly and Tania at Utea Park, I find myself in Pauly’s ute again, this time heading to Cape Rēinga.

The drive is about an hour, and I do everything I can to distract myself—talking to Pauly about his years hosting Te Araroa hikers, Tania’s iwi (tribal group), and even the negative impacts of avocado farms on the availability of water in the Far North.

It works. Before I know it, we’re pulling into the car park at Te Rerenga Wairua (Cape Rēinga).

The sight of the toilet block is a welcome distraction. A last flushing toilet before I’ll have to rough it in the wild!

To my surprise, Pauly exhibits a distinct lack of emotion, wishing me a cursory good luck before driving off out of sight.

Then it hits me—I’m on my own. Alone at the top of the world.

This isn’t unusual for the Cape. They don’t call it the Far North for nothing – it’s miles from anywhere of consequence and apart from the hoards of tourists that arrive on packed tour buses throughout the day, the Cape is usually reasonably quiet. It’s one of the things that draws me to it.

But I’ve never seen it this quiet.

Chapter 2: Where the Spirits Leap

I head down a temporary path cut through scrub to the famous lighthouse, catching a glimpse of the peninsula which is empty except for a few tourists. I realise I’ll have it all to myself when I get there—a fitting start to this journey.

Standing at the lighthouse, I reach out and touch its cool metal, grounding myself. It seems important to do this, to connect in some way to the northernmost terminus of the trail.

The Cape Rēinga lighthouse is iconic in New Zealand, but also to TA thru hikers because it marks the physical start of the Long Pathway. But it’s iconic to me in a different way.

Te Rerenga Wairua/Cape Rēinga is an immensely spiritual place. It’s been a special part of my life since I was a little girl, and I have so many memories attached to it. I’ve never been able to explain the feeling I get whenever I’m there. Perhaps I’m tuning in to the spirits of Māori souls who travel the length and breadth of the country to the Cape on the way to their final resting place. It’s at Cape Rēinga that the spirits leave the mainland on their way to Hawaiki (which is where Te Rerenga Wairua gets its name – the leaping off place).

It occurs to me I’m not really sure I’m ready for what lies ahead, but I immediately shrug it off. That’s enough personal introspection for now.

Distracting myself, I pull out my phone, steady myself and hit the record button.1 But the words stick in my throat. I just about make it to the end before choking up.

Then Scott, a Canadian traveler, appears. He’s seen my camera and asks what I’m doing.

“I’m about to start walking to Bluff,” I say with a shrug of my shoulders.

His mouth drops, and in the split second between watching his reaction and realising the gravity of what I’ve just said, for the first time it really sinks in.

He asks if I’d like a photo to commemorate the occasion. I’m again overcome with the significance of the moment. Here is the first (and probably only) person who’ll witness me start this journey. I agree, and take up a position underneath the sign pointing to Bluff.

Putting on a brave face for ‘that starting photo’.

Scott captures a poignant moment as I take in the fact I’m now on my way.

After dropping my pack in the shade and taking a moment to apply a thick layer of sunscreen,2 I give the lighthouse one final pat and then place my right foot out in front of my left and take my first step south.

This is it—my first thru-hike, my first real steps on the trail. There’s no turning back now.

As I carry on up the path two thoughts enter my mind.

First: I’ve forgotten to turn on tracking on my Garmin GPS! I’ll be tracking my progress on this journey, not just so my family can keep tabs on me and make sure I’m safe, but in case I get lost.

Second: I don’t remember there being so much uphill at Cape Rēinga! I puff and pant my way up the hill to the Te Paki Coastal Track trailhead under the almost 15kg / 33lb weight of my pack. Bugger, I’m already regretting this.

Chapter 3: The Te Paki Coastal Track and the Hell Dunes

The Te Paki Coastal Track is truly breathtaking—sheer cliffs drop away on my right to the crashing might of the Tasman Sea far below, the lighthouse still peeks out from the peninsula behind me and a sweeping golden beach lies ahead.

It’s hard to make any real progress. I stop constantly for photos and videos.

I’m descending all the way down to Te Werahi Beach, and soon I set feet to sand. The rocky outcrop which catches so many thru hikers out is just ahead.3 I’ve timed it just right – the tide’s definitely coming in but I still have a bit of leeway to get around.

My first taste of beach walking is short and pleasant. The sun beams down and the waves gently lap at the shoreline. There’s a slight breeze, but all is otherwise quiet. I see some figures far ahead winding their way up the golden mass of Herangi Hill and sigh slightly.

Te Werahi Stream at the far end of the beach is wide but not quite shallow enough to keep my feet dry. On the other side I climb a short way up the hill and find a spot for a quick rest and snack. I’ve been walking for less than an hour.

The lighthouse is still clearly visible. I take a good, long look at it. Soon, it will disappear behind those distant hills, and the next one I see will be at Bluff.

Two figures approach from the beach. One’s a tall middle-aged man (Joe), and the other an equally tall and slender woman (Julia). Joe has previously thru hiked the Appalachian Trail. Julia is from Germany and this is her first thru hike.

We decide to tackle Herangi Hill together.

Herangi Hill is actually one gigantic sand dune, an extension of the Giant Dunes I’ll walk past tomorrow on Ninety Mile beach, and a typical feature of this region. It sits between Te Werahi and Twilight Beach, just under the promontory known as Cape Maria van Diemen.

It’s fair to say I’m not expecting the challenge, and I later name them the Hell Dunes.

Herangi Hill acts like a mirror, reflecting the harsh and already strengthening sun back at us. There’s no shelter, no shade. Every step is like walking in quicksand, the sand burning beneath my shoes.

And there’s no shade, no vegetation for miles. I’m so grateful for my wide brimmed straw hat (modified by Mum with an elastic chin strap) which I almost decided to leave behind.

In a particularly rough moment, when I’ve stopped for the second time in ten minutes to take a swig of water, Joe barks orders at me to switch to a water bladder.

“You’ll never make it to Bluff like that!”

It stings, but he’s right—if I stop walking every time I need a drink I won’t get very far. His words remind me of how out of my depth I feel.

One of the big fears I’m fighting through on this adventure is the impact of Graves Disease, a condition which causes hyperthyroidism and a racing heart. Yet here I am, only an hour in, and I’m worried I’m pushing myself towards a heart attack.

We eventually take a break in a small patch of shade underneath a stand of manuka which is no more than shoulder-height. As I’m eating lunch, I pull my brand new knife out of its sheath to cut a piece of cheese… and promptly cut straight through my virgin dyneema food bag.

It’s demoralising.

It’s a downhill walk from there to Paengarēhia / Twilight Beach.

Chapter 4: Twilight Beach

When we arrive at Twilight Beach Microcamp in the early afternoon we meet Marcus, a fellow hiker. Climbing the short wooden staircase at the far end of the beach, we arrive at a raised grassy plateau and take a seat under the rotunda overlooking the sea.

To my relief, Joe decides to push on further towards Ninety Mile Beach, but Julia and I decide to stay for the night, grateful for the shelter (and the guaranteed water supply).

A German couple carrying absolutely enormous packs are already there when we arrive (in fact, we’d met them at our lunch stop) and throughout the afternoon a number of others arrive including Haley (another ex-AT hiker from Texas), two other young European women named Michelle and Jule, and a solitary young man who’d already had a rough start, and would ultimately end up quitting the trail the next day.

As the sun begins to set, we swap stories and then wander down to the beach. It’s the first real sunset I’ve ever witnessed, one of those ones you see in Africa where the sun forms a perfect semicircle as it sinks below the horizon.

For a moment, everything feels right.

I settle into my tent for the first time, trying to get everything just right. My sleeping pad is a little too inflated, then not inflated enough. So is my pillow. I adjust, and readjust but can’t quite sort it.

Alas, the night is far from restful. As soon as darkness falls a hoard of possums begin fussing around our tents, scratching to get at the food I’ve so carefully packed away. Their rustling keeps me half awake all night, and I begin to worry I won’t have the energy I need for the first real distance I need to travel tomorrow.

Day 2: Twilight Beach to Maunganui Bluff

Chapter 5: The Grind Begins.

The morning comes too soon, but I feel surprisingly energised. Today, we have 28 km to cover—and it will be our first full day on Ninety Mile Beach.

Julia and I set off early, in an eager attempt to beat the heat. But it takes me longer than expected to break camp, and we eventually leave around 7:30AM leaving Haley (who has opted for a more leisurely start) behind.

The day begins with a gentle but steady climb to Tiriparepa / Scott Point, where we get our first breathtaking views of the endless stretch of Te Oneroa-a-Tōhē / Ninety Mile Beach.

There’s a long and steep staircase down to the beach, where the dying embers of a fire betray an overnight camp, and we run into our two German friends again briefly.

The moment our shoes hit the sand of Ninety Mile Beach it’s another pinch-me moment. I can’t believe I’m finally here! I’m enjoying the feel of it: the difference between the hard and soft sand under my feet, the cacophany of crashing waves and the fresh breeze swirling from all directions.

Ahead the beach stretches on endlessly, with no end in sight.

At Te Paki Stream (the first guaranteed water spot on the beach) we take a small break. I’m hoping we can have a cuppa, but the stream isn’t deep enough to collect water without a good helping of sand, and in any case we soon spot Haley overtaking us.

Eager to keep up with the pack, we push on.

My vision narrows to a small strip. Here at the top of the beach, the giant Te Paki sand dunes mark the eastern boundary of the beach, whilst the Tasman Sea violently crashes to the west and the beach disappears into a murky haze ahead.

Our journey is punctuated only by the odd jellyfish, lying dehydrated and lifeless on the sand, or the decimated carcass of a fish which has been picked clean by the gulls.

Every now and again, a four wheel drive or tour bus passes. Ninety Mile Beach is a legal road,4 and the tour buses love bringing visitors up as far as Te Paki Stream to experience the wonder of the beach and the dunes.

Sitting in the comfort of their air-conditioned, specially built coaches, they whizz along at breakneck pace. We can see them coming from a fair distance, but it’s still a shock as they do. I imagine the commentary the tour guides are giving.

“And up ahead on our left, you’ll see a rare sight… two hikers walking along the beach. Over the next few days, they’ll walk the entire length of this beach as they make their way south to Bluff on Te Araroa…”

Occasionally I’ll glance behind me, but Scott’s Point never seems to get any smaller and the opposite is true of Matapia Island which emerges from the haze on the horizon ahead.

There’s endless time to think. And reflect.

Chapter 6: Reflections

The last time I was here I was nine years old. I tobogganed down the dunes with my grandfather, and ‘saved’ my grandmother from a rogue wave which threatened to tip her whilst we were digging for tuatua (a type of NZ clam).

They’re both gone now. But this beach reminds me so much of them.

‘The Bluff’ (not to be confused with our final destination) doesn’t appear from the haze until only a couple of hours before we reach it. By the time we get there I’m exhausted and my feet ache horribly. A wave catches me as I try to skirt around a small rocky section, soaking my shoes and adding salt to the wound.

I collapse when we finally reach camp, overwhelmed by the weight of the day.

Finding a patch of shade underneath a tree far from where the others have gathered, I cry. I cry because I’m exhausted, because I don’t know how I’ll face tomorrow’s hike, and because I know I can’t quit. There’s no way out from here other than south. I have no choice but to keep going.

I feel marginally better later on in the afternoon when I discover there’s a flushing toilet and cold shower at the campsite, and marvel at how much better this instantly makes me feel.

Plus, there’s now a good wee group of us starting to build. Haley has made it, plus Michelle and Jule (who were leaving the trail today), Marcus and a new friend John (also from the USA) who will end up accompanying us for much of tomorrow’s walk to Utea Park.

Day 3: Maunganui Bluff to Utea Park

Chapter 7: The Grind Continues

On day three, I wake with a little more determination. We have 30 km ahead of us today, and after a quick breakfast Julia and I are keen to get going. I tape my feet, hoping to stave off the first telltale signs of plantar fasciitis,5 and we set our pace for the day.

There isn’t much to say about hiking along a (mostly) featureless beach for a hundred kilometres.

The days pass in a blur of sand and heat, but we make good time. Julia, John and I talk for hours on end, getting to know each other. Eventually John speeds off ahead, and in his absence Julia and I discover that we have more in common than we thought.

We’d also decided to experiment with logistics for the first time, choosing to carry only 1 litre of water per person (we’d passed a couple of places to fill up the day before and didn’t see the point in carrying more than we needed) and slowing our pace from the hell-for-leather trot we’d adopted for the first two days.

On the western border of the beach through its middle reaches is a set of protected dunes and then the Aupouri Forest. Thru hikers are not allowed to camp here or enter the dunes, due to their fragile nature.

Which leaves the options for toileting reasonably voyeuristic. On the first day, each time the urge took us (thankfully only for number ones) we’d high-tail it to the furthest edge of the beach and gesture to the other to look away as we dropped trousers. By our last day on the beach, we didn’t care if we both went at the same time almost next to each other.

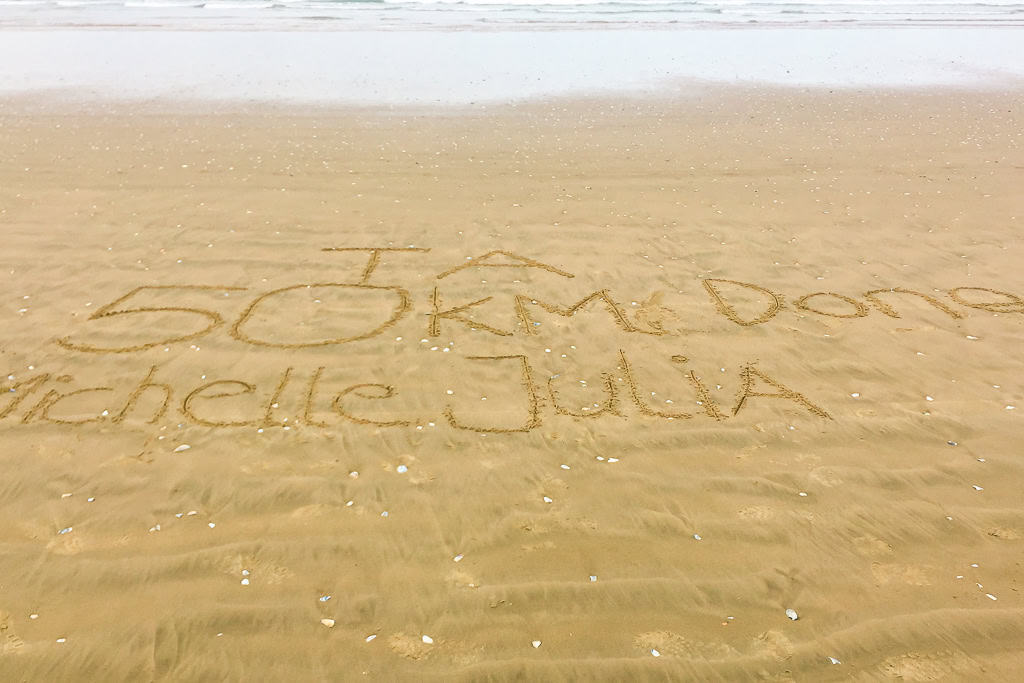

At the 50 km mark, we stopped to take a celebratory photo—halfway through Ninety Mile Beach. It feels like a huge accomplishment, but the day isn’t over yet.

The final stretch to Utea Park is brutal. My feet ache, my legs scream. Something is going on with my feet and ankles, an odd burning sensation. But I have neither the energy nor the inclination to take my shoes off, so it will have to wait until I get to camp.

We’ve already figured out that the only way to beat the beach is to distract ourselves: either with audiobooks, music or podcasts, or by walking to a strict schedule: Walk an hour or two. Stop for 20 minutes. Walk another hour or two. Stop. Have a lunch. Walk an hour. Stop.

On this particular stretch, we decide that this is best done by leaving messages in the sand to help motivate Marcus, who we know is behind us and struggling.

There are also many more dead fish and jellyfish today, although we’re lucky not to see any washed up seals or sharks as some others did.

In addition to the rash on my feet (which had been burning since we started this morning) I now also have a niggly twinge in my right knee, which I’m pretty sure is due to the strain of the natural camber of the beach:

The odd car and ute whizzes past us at pace, and towards the middle of the afternoon we spot Marcus’ beaming face inside one of them, waving enthusiastically at us as he passes.

We never see him again.

Chapter 8: A Haven at Utea Park

By the time we finally see the telltale green flags of Utea Park in the distance, I’m limping badly. It really is a sight for sore eyes (although it still takes us an hour to get to the beach exit).

Collapsing on the same ratty old sofa in the camp kitchen, this time grateful for its softness, I feel a strange mix of pride and disbelief. I’ve walked further in the last three days than I ever have in my life!

As I inspect my red and rash-covered feet, I can’t stifle the thought that there’s still so far to go.

John and Haley arrived long before us, but they’ve clearly pushed themselves — a clear expression of exhaustion covers each of their faces.

After soothing myself in the luxury of a hot shower, Pauly shows the others to a small bunk room near his kanuka oil still, and then escorts me to their private residence where I’ll spend the night in the strangely empty upstairs living area entirely on my own. This is part of the transport & accommodation package provided by Utea Park, but it seems they’ve overbooked my pre-planned cabin.

I’d rather be with the others, but it’s a good opportunity to phone Mum. It’s only been three days, but it feels like a lifetime. I try to tell her as much as I can about everything that’s happened so far, but soon realise it’s impossible.

There’s a tinge of uncertainty as well. I’m sore, my body aches, this rash is problematic and I have no idea how I’m going to walk another 32 kilometres tomorrow.

As usual, though, Mum has just the right words.

“Michelle, I’ll be honest. I was expecting you to give up at Cape Reinga. But here you are. You’ve made it the first three days. I have no doubt you can do this… if you want to.”

Only three days into this adventure, and for the first time I truly appreciate that she’s right.

Day 4: Utea Park to Ahipara

Chapter 9: The Final Push

Our biggest day yet is ahead of us. But nothing’s changed overnight.

My body is still screaming at me (the burning rash on my feet is clear evidence of that) but I pack my bag and get ready to leave regardless, determined to push through.

Determined to leave first and get on my way, I rise early and convene with the others for breakfast. To my surprise, I am the first person to leave. But Haley, John and Julia catch up quickly, and although we walk together for a short way Haley and John eventually stride ahead, while Julia and I keep a steady (but slower) pace.

We have an option to split today in two by camping at Waipapakauri, a small holiday settlement about half way to Ahipara. It’s a good-looking option, but I resolve to see how I feel when I get there.

The morning drags on and I don’t look at the time or my map for a long while. The pain and boredom is punctuated only by the odd toilet and snack break.

By mid-morning, we’ve arrived at Waipapakauri. A tiny patch of shade beckons under a small sapling near the toilet. I collapse into it, a waft of ammonia rising around me as I realise this is probably the local canine toilet too.

Now, though, our problem is water. We can’t find anywhere to fill up. The holiday park is closed, and the tap in the public toilet is running brown. Against our better instinct, we decide to use an outdoor tap at a nearby house.

The holiday park closure and water situation means we have no choice but to push on.

Chapter 10: The Never-Ending Ends

Back on the beach, the houses of Ahipara are in sight, but never seem to get closer. John has asked to walk with us, and distracts us with his jovial personality for a while, before eventually leaving us behind.

Poor Julia is stuck with me at my snail’s speed. I might as well be crawling.

After another hour I stop dead, frustrated, throwing my trekking poles into the sand. Julia follows and we share a brief moment screaming choice words at no-one in particular before resigning ourselves to our fate. There’s nothing else to do but keep walking.

Finally, the beach ends. Just before the exit to Ahipara a cold freshwater stream bisects the beach and I wade in, crying from relief as the cool water soothes my burning feet. John celebrates by taking a dip in the ocean, and I echo the sentiment by wading in knee-deep.

Ahipara township is still another two kilometres down the road, and when we finally arrive I collapse into a chair outside the local fish & chip shop. When energy allows, we each order a burger and chips. They never tasted so good.

We’ve inadvertently passed the holiday park on the way into town, and after debating whether or not to hitchhike through to Kaitaia now, we settle on staying at the Endless Summer Lodge. Blaine, the owner, kindly offers to collect us.

Endless Summer is a beautifully converted kauri villa right on the beach. As we arrive, Marley the border collie greets me. She reminds me instantly of our girl back home. Suddenly I feel like everything’s going to be okay.

It’s still early when we finally drop our packs on the floor and collapse onto our beds in one of the upstairs bunk rooms. It’s all I can do to waddle a few steps to the bathroom for a well-earned shower (complete with cold blast to soothe my still-burning feet).

As the sun drops low in the sky we lounge in hammocks watching the light fade, looking with wonder at the long sweep of beach we’ve just spent four days walking.

As the sky darkens, a crescent moon rises, and for the first time all week, I sleep like a baby.

Watch This Section on YouTube

Footnotes

- I documented my entire journey on Te Araroa in a series of YouTube videos on my YouTube channel. Click here to start watching Series 1. ↩︎

- New Zealand sits right underneath the hole in the ozone layer, so UV rays are very strong here in comparison to other countries in the world. My Dad has a running thing where he’s always ended up with serious burns to his (bald) head whenever he’s returned to NZ after a long period away, because he forgets how strong it is. Aside from blisters, one of the most common ailments you’ll see on TA hikers when they reach the end of Ninety Mile Beach is severe sunburn. ↩︎

- The Trail Notes specifically mention you need to time your departure from Cape Reinga to coincide with low tide, otherwise this section will be impassable. The rocks are covered in sharp baby mussel shells, and clambering over them is not advised (or really even possible). If you miss the tide here, it’s a long slow slog through overgrown sand dunes to get back to the trail closer to Twilight Beach. ↩︎

- Walker caution is advised, especially in the upper reaches of the beach. Cars and vehicles can travel up to 100 km/hr on Ninety Mile Beach and whereas you can see them for miles it pays to make yourself as visible as possible. ↩︎

- I’m wearing Altra Lone Peak trail runners on this thru hike, and they are famed for their ‘zero drop’ construction (meaning there is no difference in height between the heel and toe. Many people develop plantar fasciitis as a result, which can end a hike if not addressed. I noticed it was particularly bad on surfaces which were hard and compacted, like the sand near the high tide mark on the beach. ↩︎